The Return of Aristotle

- Peter Critchley

- Jun 4, 2019

- 10 min read

Updated: Dec 31, 2020

Thank you Edward Feser for the arguments presented in this new book Aristotle’s Revenge.

We’ve had Plato’s Revenge with William Ophuls’ book. Now this. There's something afoot. I started out with the modern philosophers, only to see how their thinking ran into the sands time and again. Every attempt to move forwards went the same way. I found Marx the most interesting of all of them, but found his work to come with a certain flavour that was out of kilter with modern atomism and accidentalism. So I went back to discover the pre-modern philosophers to be much more rich and rewarding than the moderns. Marx may not like it, but what I enjoy about his work is its disguised metaphysics and Judaeo-Christian ethics. That is its most appealing and most enduring quality. So why not just go direct? And Marx is very much an Aristotelian, too. I developed the implications of that in terms of an essentialist metaphysics in my PhD thesis. That’s how I earned my spurs all those years ago. I don’t feel like taking ‘revenge’ on those who opposed me with their fashionable post-everything nonsense, nor even the liberal philosophers who still insisted that Marx was a totalitarian enemy of liberty. But I was very much aware of the fact that I was swimming against the tide in the 1990s. The tide now seems to be turning, and not before time. And I feel somewhat vindicated. So, praise to Edward Feser. And I’ll take the opportunity to praise myself. Because it has been a long, hard, and lonely road to travel. There were easier paths available. But they weren’t right.

“How significant is Aristotle? Well, I wouldn’t want to exaggerate, so let me put it this way: Abandoning Aristotelianism, as the founders of modern philosophy did, was the single greatest mistake in the entire history of Western thought.”

Edward Feser

Like I’ve been saying since ever.

I won’t write much here, just simply encourage people to read this article and seek out Feser’s book Aristotle’s Revenge. I don’t need to write much, in truth. What Edward Feser is saying in his new book is precisely what I have been arguing for years. This has been my argument for an essentialist metaphysics my entire life, a view which has infused every book I have ever written. I began with Marx and found the idea there. I traced it back to Aristotle, and I remained in the company of Aristotle, then Plato. I then brought it forward to St Thomas Aquinas and discovered the peerless poet-philosopher Dante Alighieri. In time, I came to see the concept of ‘rational freedom’ that is at the centre of my philosophical work is actually a restatement of the natural moral law within modernity, but not necessarily against modernity. I retain a soft spot for Kant, despite the fact his grasp of Aristotle was limited, and I have a very soft spot for Rousseau. Marx remains interesting, vital, potentially emancipatory, potentially disastrous, depending on how you read him. I temper his love of power with the power of humility. Which is another way of saying I have left Marxism and embraced an explicitly God-centred view.

Aristotelian teleology is a Platonic idea in the designing mind of God, giving us a view that integrates immanence and transcendence so to enthuse the universe – and human beings – with spirit and purpose. As St. Thomas Aquinas and Dante Alighieri knew, and as I have been telling anyone prepared to listen for more years than I care to remember.

I won’t write a long and dense text here, I’ve done that in the many and various writings on Plato, Aristotle, St Thomas Aquinas, Dante, on moral ecology, on teleology, on religion, and, most intriguingly of all, on Marx. Marx, I insist, is an Aristotelian and an essentialist. And yet he insisted on the scientific nature of his investigations, praising Darwin for putting the final nail in the coffin of teleology. That suggests to me that Marx was very much one of the moderns, and therefore as dangerously deluded as the rest of them in thinking truth and value to be mere praxis-based projections upon a meaningless universe. The fact that he was the best of the moderns may make him the most dangerous of all of them, committed as he is to the realization of an emancipatory project that is fundamentally unrealizable. As I repeat endlessly: you cannot have your transcendent cake and eat it too. Once it’s gone it’s gone, leaving us with nothing but intractable power struggles over whatever invented purposes and principles we choose.

You can find me writing at length on these questions in my various books and articles and posts. Here, I shall content myself with some short observations and insist you read this article.

The people I address on the left in politics here really do not care for this kind of thinking, even though I demonstrate at length that Marx’s emancipatory politics are underpinned by an essentialist metaphysics. Marx himself seems not to have cared for such metaphysics, either, even though he must, surely, have known it gave him the critical and ethical strength to sustain his analyses in such depth as to yield such powerful conclusions.

If the left still refuse to come near such thinking, dismissing it as metaphysical or, worse, theological – heaven forbid if, after putting God to death all those years ago, Providence ends up making a much needed return - then that is very much their loss. Because I argue that the ideals and values that ‘progressives’ argue for are not actually progressive at all, they are merely attempts to call the world back to true law and order. They are attempts to call back the soul. For ‘emancipation,’ read ‘salvation.’ The sooner we understand this the better it will be for all of us.

I have tried my best to get people to see this. I don’t feel I have had much, if any, impact, and many still wear their atheism as a badge of their radicalism. It’s not radical at all, the very opposite in fact, often (not always) betraying an analysis that remains stuck on the surface level. There is such a thing as moral truth and moral knowledge, and there is more to the world than physical explanation and fact. There is a future for those who understand this. Mathematician A.N. Whitehead took his former colleague Bertrand Russell to task on this. In Science and the Modern World, Whitehead wrote that man may not live by bread alone, but nor can he live by disinfectants. Read the last passage in Russell’s History of Western Philosophy. It is clear that Russell’s philosophy was all about disinfectants. He thought that this was the way to avoid rival fanaticisms and fundamentalisms drowning the world in their hatreds. He was wrong, profoundly so. A dreary logical positivism or atomism leaves human beings without meaning, without purpose, having to cope with the despair of journeying on a destinationless voyage. That's an invitation into entertaining or exciting ersatz nonsense. I have a friend who told me that no one has ever killed anyone in the name of atheism. No one does anything in the name of atheism, was my response. Atheism is a negation (the atheism that does not feel the need to name itself is different entirely, and is life-affirming - that's the view I respect, although I still argue it falls short).

It is easy to condemn the fanaticisms of others. But collective human movements come in much more positive forms, too. Please read my many posts below on this. I constantly emphasize the motivational economy and activating the moral-psychological springs of action. A science-centred culture misses these, informing passive minds with facts and then standing back as if action will follow. It won’t. And those who keep pressing their emancipatory politics on the basis of the modernist-scientistic line that sets us within an objectively valueless, purposeless, and meaningless universe will continue to fail.

Please read the article. Science is only possible because it is intelligible to intelligent creatures. Why is this so? Once we move beyond fact to questions of value, meaning, and significance we have moved beyond the realm of science. Modern scientific method can only take us so far with questions like that. But those questions are key. Because science and the value and point of science depends upon them.

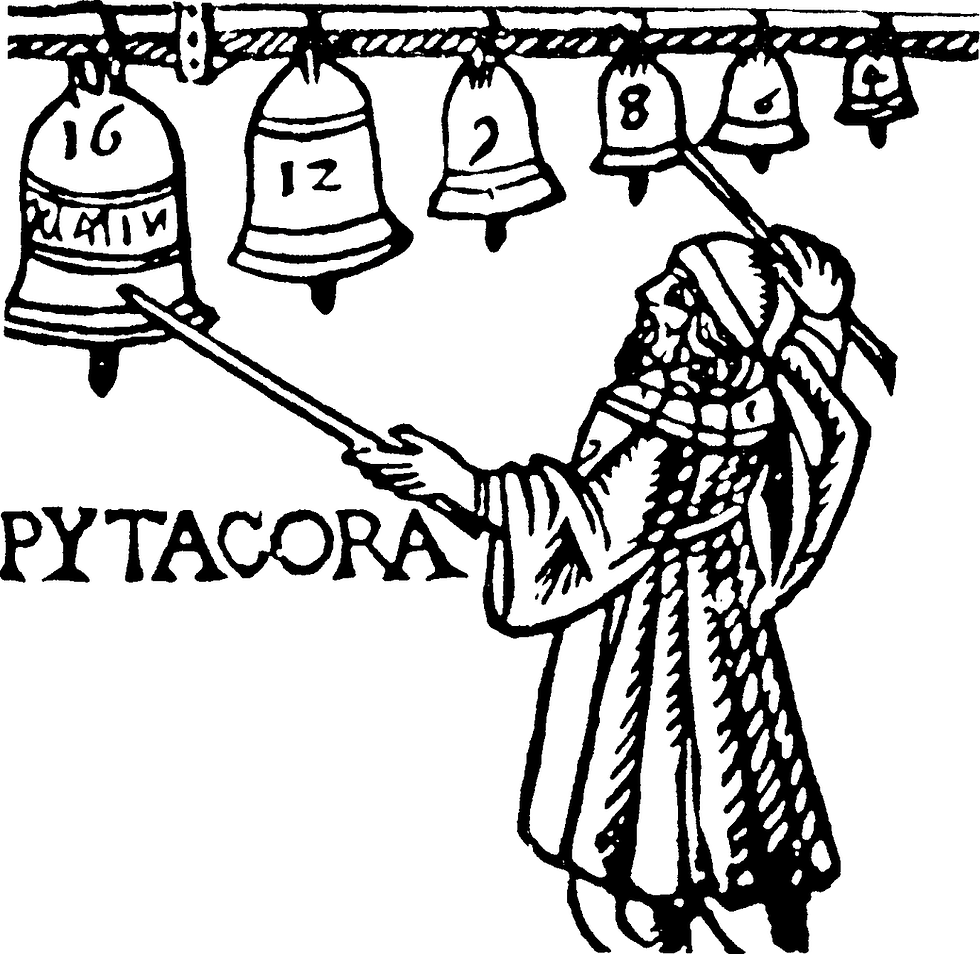

Some ideas transcend the realm of nature. Kant discovered the scandal of reason, which refers to the fact that the mind raises questions which are beyond the capacity of reason to solve. Nature is wonderful and natural science yields a wealth of knowledge about it. But that is not the end of the matter, only the beginning. These are the easy questions. Nature’s rich diversity is wonderful. But we also wonder: how is there purpose in the universe? Aristotle was the first scientist, and he marvelled at nature’s rich diversity. And he marvelled at all things, great and small, because in all things there is something of the divine.

I’ll go with Aristotle on this. Also Roger Trigg and his excellent book Beyond Matter: Why Science Needs Metaphysics. Foundational truths are not just physical, they are metaphysical. I agree, although I would need some further philosophical work here to clarify what is meant by foundations. We have been seduced by modern natural science into believing that we can have complete natural knowledge, and that this knowledge is the only true knowledge. Now we have discovered that science cannot perform the God-trick, and that in a ceaselessly creative universe we live forwards into mystery, many are panicking and claiming that since there no foundations that anything goes. They call it postmodernism. It used to worry me. Until I realized that the postmodernists, whether they knew it or not (maybe Levinas did, and Derrida, if they count), were telling us something we should know – we lack foundations and we always did. God and religion were never foundational in this modernist sense. We need to recover the approach which cleaved to faith and reason. And Kant, too, remains indispensable in pointing to an innate conceptual apparatus which is integrated with the intelligibility and structure of a universe shot-through with purpose. But Kant needs a strong dose of Aristotle and St Thomas Aquinas to save him.

We are getting back to where we ought to be. We’ve taken a detour into the Megamachine and its mentality. We may yet get out.

As to the notion of Aristotle’s Revenge, I feel entitled to write of ‘Peter’s revenge,’ because this is the message I’ve been trying so hard to bring to the world. On my “About Me” page you will find this quote and comment from me:

“Time out of mind it has been by the way of the ‘final cause,’ by the teleological concept of end, of purpose or of ‘design,’ in one of its many forms .. . that men have been chiefly wont to explain the phenomena of the living world: and it will be so while men have eyes to see and ears to hear withal. With Galen as with Aristotle, it was the physician's way; with John Ray as with Aristotle it was the naturalist's way; with Kant as with Aristotle it was the philosopher's way. ... It is a common way, and a great way; for it brings with it a glimpse of a great vision, and it lies deep as the love of nature in the hearts of men.”

—D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson, On Growth and Form, 1942

…. as with Aristotle … I shall return to ‘the Philosopher’ throughout. In my writings I attempt to apply rather than restate Aristotle. It’s sufficient here to point out that Aristotelian essentialism permeates my work.

It does, too.

Feser painstakingly demonstrates the importance of Aristotle’s fundamental ideas to science and philosophy, especially when illuminated by St. Thomas Aquinas’s classic explanations and developments of them. Please read my Aquinas, Morality, and Modernity from 2013 on this. You’ll find the link on the Books tab. Yet many lazily repeat the claim that Aristotle’s concepts are out of date. It’s second hand and second rate philosophy, but easy, hence possesses a certain popularity.

Feser’s book painstakingly demonstrates just how wrong that claim is. For example, take the fundamental concept of teleology, which refers to the range of purposes that philosophy and science can discern in nature.

I quote from the article:

‘the teleology we observe in nature is better described as intrinsic teleology. A prime example of such internally unfolding teleology would be an acorn, which naturally grows into an oak tree.

Aquinas harmonized both of their approaches. He spoke of nature’s creatures as being internally structured by Aristotle’s intrinsic teleology. But creation itself was extrinsic in relation to God.

The universe’s Aristotelian teleology is thus a Platonic idea in the designing mind of God.

God is the creator, externally granting and concurring with the actual existence of nature. Yet he leaves creatures free, to act according the range of their natural essences.’

Praise be. That’s what I have been saying for years. And that’s what I shall be saying in my forthcoming Dante book. Throw in the four-causal explanation and I shall go to bed happy.

This intrinsic Aristotelian dynamism I emphasize in an essentialist metaphysics is, properly understood, God as transcendent source and end which enthuses and moves all things – in God’s will is our peace, it is to God all things return. In other words there is an extrinsic force too. That is the great primal force that invests the world with meaning, purpose, with creative potential and the reason to actualize it, gives us the end and the destination to travel to. We are finding out, surely, that you cannot strip the world of meaning, value, and purpose, as a disenchanting science does, throw it over to exploitation and despoliation, to human value alone (monetary or otherwise), and then cite scientific facts on climate crisis to call on people to save the planet for sake of future generations. You have lost the motivational springs, you have lost the reason why.

‘Aristotle’s philosophical insights magnanimously encourage modern science to keep flourishing. His ideas can embrace all new discoveries concerning the diverse aspects and essences of nature. Aristotle still wins victory by equipping us with the fundamental concepts needed to make sense of any new discoveries. Modern biology, for example, cannot be understood with Platonic ideas of merely extrinsic design.

But we will rightly understand nature, if we appreciate how Aristotle already understood it best: from the inside out.’

I will just finish by noting that that is a strangely naturalistic conclusion from a Catholic article. As is said elsewhere, we need both intrinsic and extrinsic design, as given by St Thomas Aquinas and, as I shall show, which runs throughout Dante’s Divine Comedy. And throughout my own work.

I feel entitled to give myself a plug and a pat on the back here. I have been working tirelessly alone, at my own expense, for years now on this. I wouldn’t use the word ‘revenge,’ though, even though time and hard work have taken their revenge on my poor mind and body (medical appointments coming up, it will be a long road back to living well, and being valued to my true worth). I like the Aristotelian encouragement to just keep flourishing. Just flourish. I may make that my new motto to live by.