Pythagoreanism Over Time

- Peter Critchley

- May 3, 2020

- 4 min read

Updated: Dec 31, 2020

Pythagoreanism over time

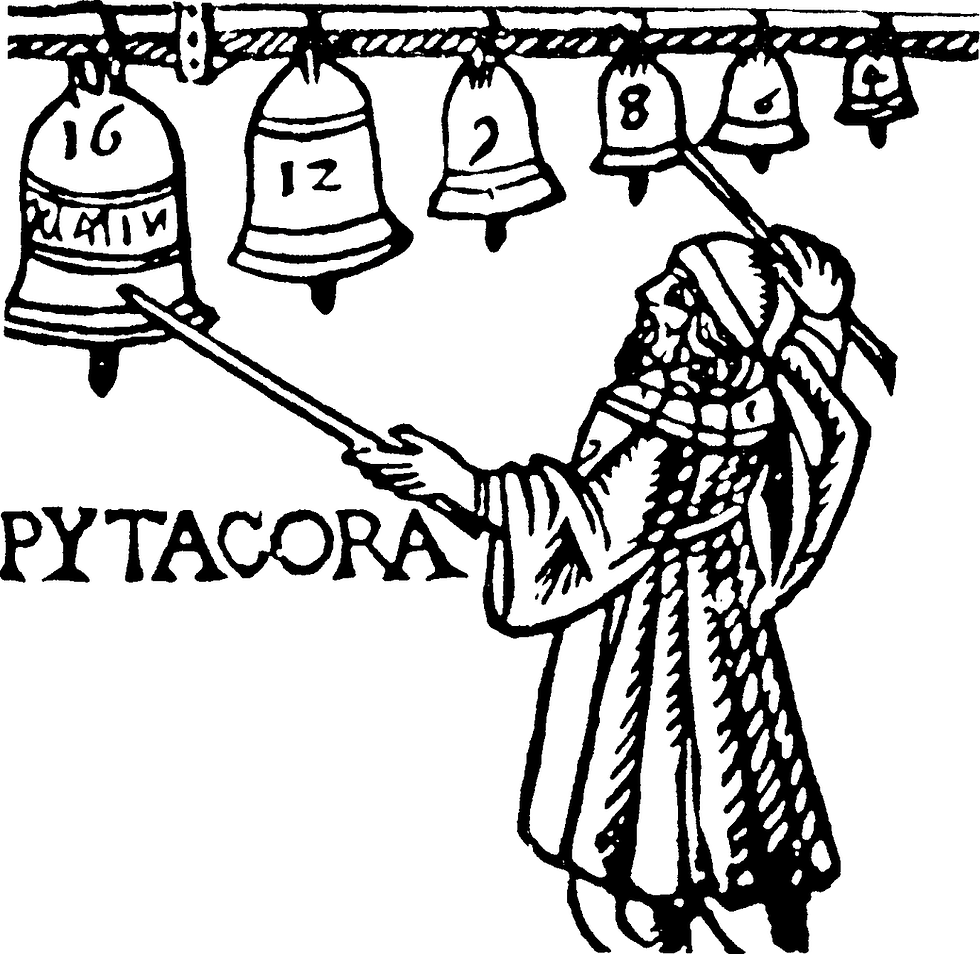

'Music is the harmonization of opposites, the conciliation of warring elements.'

- Pythagoras

Plato adopted much of the Pythagorean doctrine a century and a half after the death of Pythagoras. Plato’s eternal Ideas or Forms, of which earthly objects were mere approximations, found their perfection in the timeless truths of mathematics, with music as the bridge between this eternal realm of pure and timeless Ideas and the transitory realm of temporal affairs. In the Timaeus, Plato describes how God, as the creator-architect of the world, brought order out of chaos by dividing up and laying out the heavens and the Earth in proportion, according to the musical ratios. It is for us to train our senses and discern the order of the universe and conform our senses to it, beyond perceptions and the way they mislead us:

THE GOD INVENTED and gave us vision in order that we might observe the circuits of intelligence in the heaven and profit by them for the revolutions of our own thought, which are akin to them, though ours be troubled and they are unperturbed; and that, by learning to know them and acquitting the power to compute them rightly according to nature, we might reproduce the perfectly unerring revolutions of the god and reduce to settled order the wandering motions in ourselves. (Plato, Timaeus 46c)

Music is thus an all-pervasive force throughout the universe, yielding a world harmony that guides the planets in their courses, governs the seasons on the Earth, and orders of society and the human soul. In the same way that modern science explains natural phenomena, so the simple ratios of the musical intervals in the Pythagorean conception are mathematical expression of the inner harmony that guides and orders all natural relations.

The idea of a mathematically based musical harmony pervading the universe as a great ordering principle was taken up with enthusiasm by the scientists, philosophers, artists, and poets in successive ages, up to and including the present day. Ptolemy, whose astronomy was dominant until the Copernican revolution, wrote a treatise on music theory and the mathematics of music entitled the Harmonics. Here, Ptolemy argues for the existence of a cosmic harmony that ordered the movements of the stars and planets around the earth in accordance with musical ratios. The Harmonics opens with an analysis of pitches and intervals, from which Ptolemy extracts an idealized musical scale which he proceeds to expand by applying musical intervals to the human soul and celestial bodies, bringing him ultimately to a cosmic harmony.

In the early years of the Christian era it was St. Augustine and Boethius whose books on music were to exert a profound influence on the ideas and practice of artists and architects throughout the Middle Ages. Both formulated aesthetic ideals expressing the idea of a cosmic harmony pervading the universe, seeking thereby to lead the mind to the contemplation of the divine order. The geometry of musical consonances was presented as the Earthly image of a greater eternal harmony, with the perfection of these proportions being discernible to both the ear and the eye.

From here, the tradition is passed on to the great Gothic cathedrals of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, such as Notre-Dame, Rheims Cathedral, Chartres, and Amiens. These have been described as 'frozen music,' with the musical ratios of the perfect consonances being incorporated into the proportions of the buildings by design. These cathedrals express in stone the inner harmony of the cosmos articulated by music, sharing the same mathematical vocabulary.

The modern age is characterized by a mechanisation, specialisation, and differentiation, a disenchantment of the world that had rendered the world objectively valueless and our vision piecemeal and partial. Our aesthetic sense has been estranged from the grand vision of an all-embracing cosmic harmony, hence the pronounced tendency to take the arbitrariness of myriad perceptions as reality and notions of divine beauty, section, and proportion to be illusions. The Pythagorean legacy nevertheless survives in mathematics and music, with the phenomena of periodic vibration, resonance, and the mathematical expression of these, being fundamental in chemistry, physics, engineering, and astronomy. Whilst the Pythagorean ideal of musical proportion has given way to more sophisticated techniques, it retains a relevance and motivating power. That the divine beauty could ever be captured by our reasoning, be it mathematical or otherwise, is not only doubtful, but undesirable. To enclose the world in a totalizing human Reason is not so much a ‘divine comedy’ as an undivine tragedy. The Pythagorean vision is best considered an inspiring metaphor for the imagination rather than a claim to an objective truth grounded in scientific evidence and mathematical proof.

Lippman, Edward A: Musical Thought in Ancient Greece ; Columbia University Press, 1969

Crocker, Richard L: Pythagorean Mathematics and Music ; Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism , Winter 1963

Helm, Eugene: The Vibrating String of the Pythagoreans ; Scientific American , December 1967

Von Simson, Otto: The Gothic Cathedral ; Bollingen, 1962

Wittkower, Rudolf: Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism ; St Martin's Press, 1988

Bouleau, Charles: The Painter's Secret Geometry ; Harcourt, Brace, 1963

Coates, Kevin: Geometry Proportion and the Art of Lutherie ; Oxford, 1985