Socrates and Moral Knowledge

- Peter Critchley

- Sep 13, 2010

- 5 min read

Updated: Dec 31, 2020

As a mental discipline, philosophy began when human beings started to try to understand the world by the use of their reason, without appealing to the authority of tradition or revelation. The man considered to be the first philosopher was Thales, who asked the question "what is the world made of?" Thales drew the conclusion that everything was water in one form or another. Another early question was "what holds the world up?" Anaximander argued that the earth is not supported by anything at all. It is just a solid object hanging in space, and is kept in position by its equidistance from everything else. So original philosophy was natural science.It was Socrates who changed the direction of philosophy from the physical world to the moral world.

When the Greek comic playwright Aristophanes came to satirise Socrates, in his play The Clouds, he called the philosopher's imaginary world "Cloud-Cuckoo-Land". Aristophanes was wrong, both about Socrates and about philosophy. The revolutions that really change the world have begun in the head - or even higher up, in the clouds.

Cicero argued that: 'Socrates was the first to call philosophy down from the heavens and compel it to ask questions about life and morality.' Socrates did this by arguing that the most important question of all in philosophy is how we ought to live. “What is good?,” "what is justice?"

I want to defend philosophical thinking in two respects:

1) Philosophy is not so much a rationalist outlook abstracted from life as an ideal ‘ought-to-be’ challenging and subverting the ‘is’ of everyday reality.Beginning with Socrates' pupil Plato, philosopher after philosopher has redrawn the map of humanity with ideas; they have held that the secret of turning around the benighted vision of human beings, chained in their cave facing away from the sun, lay in the most rarefied essence of thought.

2) Philosophy in its origins was not an academic discipline removed from everyday life but a practice and a way of life. In the Prison Notebooks, Antonio Gramsci argued that ‘It is essential to destroy the widespread prejudice that philosophy is a strange and difficult thing just because it is the specific intellectual activity of a particular category of specialists or of professional and systematic philosophers. It must first be shown that all men are "philosophers".

Gramsci refers to language, common and good sense and popular religion as a kind of ‘spontaneous’ philosophy that most people engage in. Philosophy goes further than this but it is this assumption of a rational capacity on the part of each and all that the hope of making the world philosophical rests.

Socrates famously never wrote a word. What we know of Socrates comes from Plato and others. For Socrates, philosophy was not merely about abstract reason and reasoning, it was a way of life, a everyday practice. Socrates knew well that reason is far from the whole of life. Reason highlights our ignorance. But after that, a good deal rests on character and intuition.

Plato was also wary of writing. He suspected that, in the way it objectified philosophy, it could become an excuse not to live it. In the way that it tidied philosophy up, writing could become a means of concealing a meaning that can only be experienced. It is for this reason that Plato bans poets from his ideal city-state in the Republic. This may seem extreme, but poets were authority figures. The body of work from Hesiod to Homer was the dogmatic canon of the day which people remembered and recited. Plato saw the danger here of an appeal to the dogmatic instincts of citizens, instead of thinking they would use ready-made arguments.

Socrates was no ivory tower professor, but took philosophy to the people by meeting them on the streets or in the market place. He is drawn to others because it is only with others that people gain the best understanding of themselves. So for Socrates the key to wisdom is not just defining abstractions but self-understanding. In this, there is an appreciation that all human beings are philosophers, or are capable of becoming philosophers, in that all possess the capacity to reason. The first philosophers in the Socratic tradition did not expect their pupils necessarily to agree with them. Rather, they taught people to use their own reason, to think for themselves, develop ideas of their own.

To understand Socrates’ achievement, we need to understand something of the historical context. The scientific optimism of today is nothing new. The natural philosophers who came before Socrates had built a record of substantial and remarkably prescient scientific achievement.

Parmenides realised that the moon reflects the light of the sun.

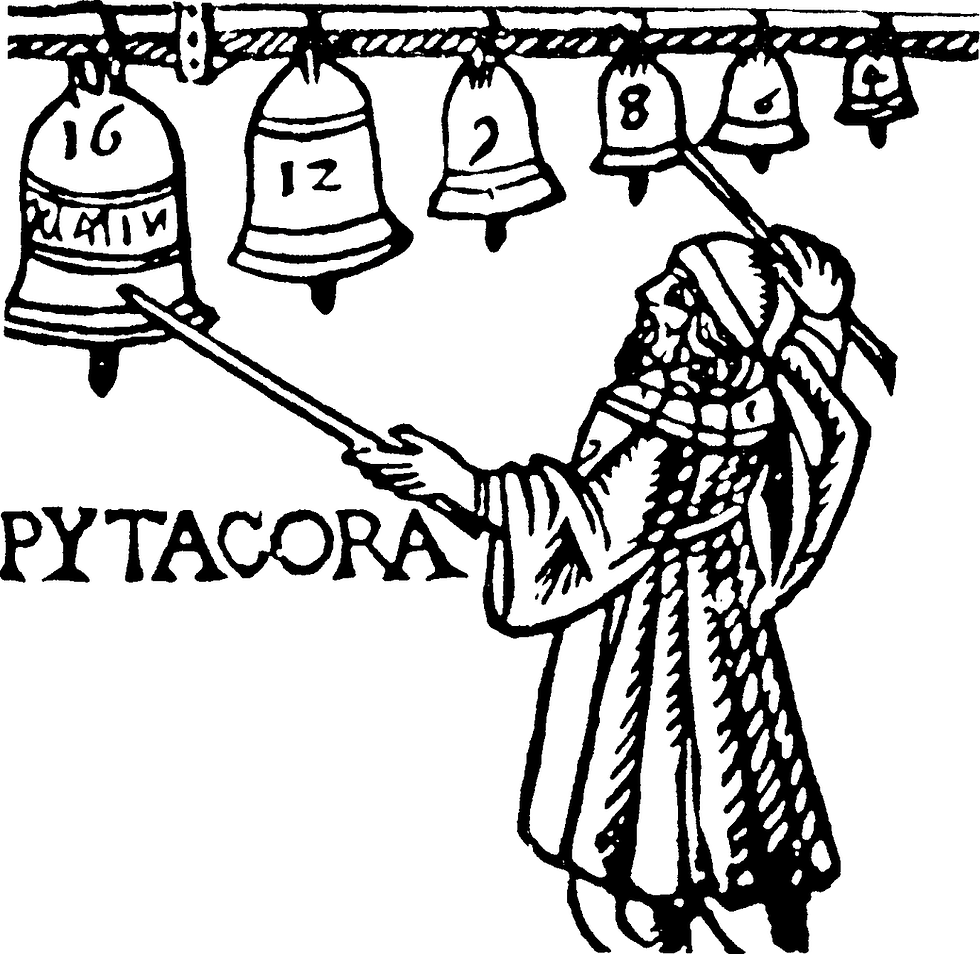

Democritus postulated the basic units of nature as atoms existing in a void. Pythagoras had worked out that day and night were far better explained by the earth going round the sun, not vice versa.

Socrates challenged not science as such but the overweening claims made for science.

But as he moved to the aspects of life concerning human beings, meaning and morality, he found scientific explanation to be not merely incomplete but, humanly speaking, irrelevant.

Socrates contemplated the limitations of scientific explanation whilst sat in prison awaiting death. If the body's chief aim is survival, then, according to the scientific world-view, Socrates’ sinews and bones should have been miles away.

The reason that Socrates was in prison had nothing to do with the physical processes of body or mind. Socrates is in prison for a reason that science does not begin to explain. The 'cause' of his predicament is a moral one. As a physical being, Socrates could have escaped and lived but, as a moral being, has decided it is right to stay and die. Socrates thus separates moral causes from with physical conditions.

When it came to matters of moral significance, science neither asked the right questions nor used the right tools.

Socrates saw that if it is meaning that you want, then it is moral philosophy you must study. Socrates created a category of knowledge to which science has no access.

So Socratic philosophy did not stop at the point at which reason could go no further. Rather, it was but part of a philosophical way of life. Socratic philosophy embodies an ethos as well as the principles of an intellectual exercise; it is a practice that can embrace the whole of life as well as an approach that can engage the mind. Plato presents Socrates to us in such a way as to nurture an ethos as well as provide an education.

Philosophy as the cultivation of a way of life seems so different to what is usually taken to be philosophy today, with the emphasis on the development of rational techniques, thought and intellectual know-how rather than on a practice that seeks to shape the person, heart and mind.

Rather than simply inform minds, Socrates sought to form characters so that human beings would think, choose and act wisely. Formation was the key to Socrates' moral knowledge, the activation of the common moral knowledge of all human beings, not some arid information of intellects that left character unchanged. To be effective, knowledge had to be affective.