Knowing History, Politics, and Human Beings

- Peter Critchley

- Dec 10, 2021

- 12 min read

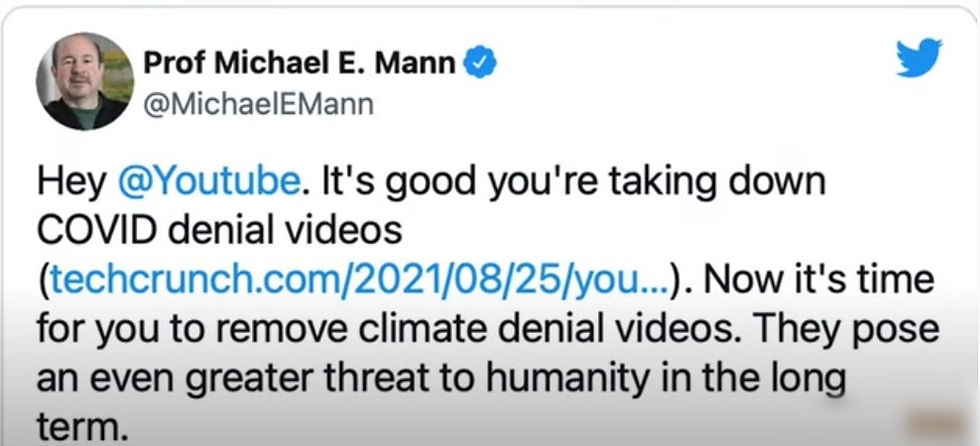

Scientist and climate campaigner Michael Mann called upon YouTube to remove what he calls ‘climate denial videos’ from its forum. “Hey @YouTube. It’s good you’re taking down COVID denial videos.. Now it’s time for you to remove climate denial videos. They pose an even greater threat to humanity in the long term.”

I’ll tell you what poses an even greater threat to humanity in the long term – would-be universal educators becoming autocrats, claiming the right to speak and act for others on account of being a knowledgeable elite, the public being deemed incapable of thinking, reasoning, and learning (learning as a change of behaviour). These self-appointed educators gearing up to be the benevolent despots of an austerian environmental regime are in our midst already and are crawling all over public debate. It seems that the only people permitted to speak in this era are those who are certified and credentialed in some way, with an institution or body behind them. The citizen voice is zero. Citizens are empty heads to be passively educated/indoctrinated with correct truths from above and from the outside. Statements such as this from Mann reveal precisely the democratic deficit at the heart of environmentalism, itself a product of the failure to take practical reason (ethics and politics) seriously.

Mann’s statement quickly came to public attention and was written up as a piece for Forbes Magazine, under the headline: “YouTube is serving up climate misinformation. This top scientist says Google should ban it.” (written by David Vetter.

If you can’t see how appallingly repellent that statement reads, then you are as clueless as Mann and his ilk. You are a fully paid up member of the wannabe autocrats seeking the authoritarian impostion of climate truth and necessity, speaking in the voice of a reified science.

I have written on this at length and am now obeying strict orders to myself not to repeat and waste any more of my precious time and energy (I have wasted years addressing these points to environmentalists and climate campaigners of various persuasions, all united by a seemingly congenital incapacity to grasp the points at issue, least of all to respect the citizen voice and understand the worth and dignity of politics. There are many reasons why such people are authoritarians. They think truth trumps all things, and extend it crudely into human social and political areas, overriding questions of values, meanings, significance, even interests and stakes. All of these things, lying at the centre of human life, simply cease to exist for all those who think themselves in possession of an overriding truth. This is both bad education and bad politics. In teacher training I was ticked off for making the objectives of my lesson plan of such overriding concern that I simply imposed them on students, ignoring whether they were actually learning anything and coming with me to the end. I was so concerned to teach the truth of the subject matter that I paid no attention as to whether students were assimilating the learning points. It is so much easier to impose truth. Indeed, it is so much easier to disregard the messy yes/no of people and politics. But the solution to bad politics is not ‘no politics’ or ‘beyond politics’ – an ideological preparation for a power-grab if ever there was one - but good politics. Likewise, the solution to bad speech is not no speech but more speech, on the humanly optimistic assumption that, sooner or later, the bad will be checked by the good and truth will out. I have confidence in the power of truth and in the intellectual virtues. I also trust the common moral reason of human beings, ‘ordinary’ people at least as much – and probably moreso – than those ideologues with a dog in the fight. Those who look to censor are anthropological pessimists whose predilection for censorship betrays their lack of faith in the common moral and intellectual reason of humanity. Such pessimism translates very easily into a preference for authoritarian as against democratic institutions. There are far too many autocrats and would-be autocrats in modern politics and far too few democrats. Everyone with a cause is expressing impatience with the need to argue for that cause with the ignorant, uneducated rabble and would prefer the short-cut of imposition to the indignities of having to engage with the great unwashed in order to persuade them. If you believe that people are fundamentally stupid and ignorant in the first place you are hardly likely to see any point in seeking to persuade them. This is what really rankles with those who think they already know the truth – the idea that people they consider lesser and inferior in some way, certainly in terms of knowledge and education, stand in the way of truth being translated into practice. That urge to censorship reveals the character of the censors precisely – on the assumption that they alone are capable of understanding truth they seek to preserve their monopoly of that truth and use that monopoly to manage and manipulate all who are subject to it.

There is no-one who loathes falsehood, lies, deception, and misinformation more than I do, which is why I have spent decades arguing for ‘rational freedom.’ In general terms this holds that, in the words of Spinoza: ‘the more man is guided by reason, the more he is free.’ That’s why I have spent so long looking at various issues, seeing the extent to which various positions are supported by good arguments. It is also why I make the field of practical reason (politics and ethics) central, arguing for the cultivation of the intellectual as well as the moral virtues so that the members of the citizen body respect the truth, enter the public realm as truth-seekers, and seek to embody truth. It is those virtues, within a moral infrastructure and motivational economy, that is so singularly lacking in the top-down, educational, science-heavy approach to environmentalism. And that is why such environmentalism a) fails in the first instance b) defaults to authoritarian imposition time and again. There is no mystery as to why, despite claiming a wealth of science and technology in its support, the educative model of environmentalism has racked up decades of failure – it is politically, morally, and sociologically illiterate. It doesn’t like human beings, it doesn’t trust human beings, it has no faith in the reasoning powers of human beings, it does nothing to cultivate the moral and intellectual virtues. ‘Scientism’ is a blight in that it is forever seeing society as a laborities, citizens as scientists, and science as doing the job of politics and ethics. That is crude, blinkered nonsense that simply goes to prove the extent to which supposedly clever people can be mind-numbingly stupid. At the heart of that stupidity is an almost complete disrespect for and disregard of common humanity. Do we really need to cite the lessons of history to caution the need to be wary of gatekeepers to truth?

Mallen Baker makes the point succinctly:

“I am not a fan of scientists calling for censorship of people who don’t accept the orthodoxy. I think scientists who call for such a thing are showing that however smart they may or may not in their field they know NOTHING – NOTHING – about politics, and they should be allowed nowhere near the levers of power.”

That statement bears repetition. It is a point I have been making for so long now I could cry – environmentalists pressing science into the field of practical reason know NOTHING – NOTHING – about ethics and politics. I would go further to argue that they know nothing of ethics and politics for the very reason they consider such realms as merely secondary and ephemeral, incapable of constituting any genuine knowledge. The anti-democratic, inhumanist, and authoritarian impulse stems precisely from that scientism. And those in the grip of scientism seem congenitally incapable of grasping the point. To argue that the gap between theoretical reason (our knowledge of the external world, science and the realm of fact) and practical reason (politics and ethics, questions of values and practices) be overcome raises the question of truth and its mediation. If freedom is the appreciation of necessity, then the key term is ‘appreciation.’ Unfortunately, those in the grip of scientism seek to close this gap by having the realm of theoretical reason – the only true knowledge – cannibalize the realm of practical reason. It is why, time and again, you see them naturalizing ethics and politics. Such a mentality moves very easily into a Social Darwinism that advocates a bio-politics or a bio-security state. The emergence of ecology as the new dismal science arises entirely from the way environmentalism scotomizes ethics and politics, seeing these in naturalist terms to be read-off from the latest science.

It’s nonsense, and mediocre nonsense at that. Not only is it politically debilitating – how long now has this approach failed to motivate and mobilize mass support? - it is politically dangerous – it seeks to go beyond ‘the masses’ to the truth of the knowledge/power elite.

You just need to ask who the likes of Michael Mann include in his category of deniers whose views should be censored and banned. I would suggest that that category comprises all of these who dissent and disagree in someway, all those who fail to accept the view claimed to be the one and true view, the new orthodoxy, ‘the one Ring to rule them all,’ what Lenin called ‘correct ideology.’ Such people make the oldest mistakes in the book precisely because they don’t know history, don’t know politics, don’t know people – because they are so myopic in their pursuit of their truth that they don’t respect anything that lies outside of that narrow purview. They are the last people to be allowed anywhere near politics and power.

Mallen Baker gives a couple of examples of those Mann would likely ban. First up is Bjorn Lomborg. I have criticized Lomborg in the past myself, and in somewhat scathing terms.

Lomborg cherry-picks his figures and his data points are contestable. But I wouldn’t censor him and ban him. It is always possible that you may be wrong and the people you criticize may be right, or raise points, issues, and arguments that are valid. Lomborg is certainly right to raise the issue of what our public policy approach should be on climate change and is certainly right to address issues of finance and expenditure. For all of the panicky talk about dwindling carbon budgets, the fiscal budgets of states are also limited and there is a real danger of being panicked into expensive climate programmes that are not only ineffective but waste resources that are better targeted elsewhere. Those questions need to be addressed and debated openly, with action proceeding on the basis of consent on the part of those not only subject to those climate policies but paying for them. When the people who are making huge demands on governments in terms of ambitious and expensive climate policies and programmes seek to silence critical voices, there is a need to be sceptical. You may disagree with Lomborg – I have in the past – but disagreement and dissensus is politics and debating contrary platforms with a view to discerning truth and formulating a commonly acceptable position is a fundamental part of what politics is all about.

Baker goes on to mention Michael Shellenberger, whose advocacy of nuclear power isn’t to the taste of environmentalists like Michael Mann. It’s not to mine and I have argued against it. You are entitled to argue for and against; what you are not entitled to do is silence those who argue against your position. It is interesting at least that environmentalists who are so big on being out of time on climate, who make ‘necessity’ the key figure of their climate ‘non-politics,’ are so adament in ruling out nuclear power. That gives grounds for suspicion that we are in the realm not of science but of a politics that dare not identify itself as a politics lest it lose the authority of science it claims (and reveal itself in all its political feebleness at the same time – ‘we’ve tried politics/the democratic process and it’s failed,’ say activists waging a war of attrition against the public, when what they really should be saying is that ‘we’ve done politics incredibly badly, failed to respect the autonomous citizen voice, and failed for completely predictable reasons’).

Shellenberger’s argument for the need for reliable energy for the poor, even if that means using fossil fuels, is also not an argument that environmentalists like Mann are prepared to entertain. There is zero evidence that such environmentalists give a damn about ‘ordinary’ people and the impact of climate austerity measures and taxes upon their lives. Why should they? There is an inhumanism at the heart of this environmentalism. They get misty-eyed over a ‘Mother Nature’ that is entirely indifferent to human needs and cares, but become most strident when it comes to doling out hard lessons to real human beings. In this miserabilist worldview, everything is a legitimate agent in Nature apart from human beings. To think that this is the radical opposition to the capital system! Marx must be turning in his grave, wondering where on Earth the Left went. This is regressive, reactionary drivel.

The taste for censorship on the part of some in the environmental movement begs the question of what other powers these people would claim for themselves as they seek to govern the bright clean Green Megamachine. You certainly do not give the power of censorship to activists whose campaigning imperatives blind them to the difference between deliberate and dangerous misinformation and political views which are simply different, the very stuff of politics. And in any case deliberate and dangerous misinformation is to be checked openly in the public square – if public life is not self-cleansing by way of rational discourse and debate, then there is no hope anyway and we might as well just give up. The fact is that dissensus and disagreement is the very stuff of politics, meaning that each and any of us can fall foul of any prevailing or would-be orthodoxy in any time and place. That’s why the rules on censorship need to be clear, simple, and minimal – aimed against those who openly and directly call for violence against another person or aim to do harm. And harm here means harm, physical harm, and not the ‘harm’ that mollycoddled students used to getting their own way and unused to formulating arguments in support of their case claim to feel when someone expresses an opinion that doesn’t conform to their truth.

Seriously, this situation is becoming too daft to laugh at. It seems that, long before we get down to the real business of truth-seeking, arguing cases with a view to attaining ‘rational freedom,’ we are going to have to re-establish some basic conditions of truth-seeking publicly. Again, I am very well aware that this will place me alongside some people with whom I have disagreed vociferously in the past. Indeed, I have frequently and publicly noted how many of those who make such a big thing of free speech are among those to be found readily abusing it, inciting others to call for censorship as a response. I have often quoted Kierkegaard in this respect: “People demand freedom of speech as a compensation for the freedom of thought which they seldom use.” I make a distinction between free speech and good speech, placing the emphasis on good speech.

I urge those making such a big thing of free speech not to abuse that freedom with bad speech, seeking to propagate bad ideas and false information, leading people astray. But to insist on good speech is not to argue for the censorship of bad speech at the same time. In a sense, I believe in the self-censorship that comes from the possession and exercise of the intellectual and moral virtues, something internal in person and society rather than an external imposition by way of a societal, institutional, and legal regulation.

So there I am, advocating against censorship in favour of free speech with people with whom I have vehemently disagreed in the past, and will no doubt disagree in the future, suspecting all along that they would be most unlikely to respect my free speech should they ever get the power of censorship in their hands. The truth is that a modern society brought up on the notion that each person is able to choose the true and the good as he and she sees fit is becoming dangeously neglectful of some extremely important practical truths won by hard experience in the past – not least that each and any of us may well be wrong in our views, no matter how strongly we hold them. Human beings are fallible. And if you are not questioning, then you are not doing science, you are presenting authority. There is a need to defend this hard-won understanding and the time-honoured principles it has yielded. Always, there is a need to establish, nurture, and sustain good process as well as identify truth and seek its public recognition and incarnation. It is the easiest thing in the world to support a conclusion or a result with which one agrees; it is a fatal error to ignore the process by which that conclusion or result is attained. Sooner or later, bad process will come and bite you on the backside, consuming good ends to become the end in itself – a very bad end.

Know politics, know ethics, know history, know people – and if you lack knowledge in any or all of these areas, stay the hell out of public life, because you are a blight.

The quotes from Mallen Baker can be found here

I examine these questions much more deeply here. The critical essays collected here will make uncomfortable reading for those who are part of mainstream environmentalism, but necessary reading – because the genuine potentials for the ecological transformation of the political are being bungled and botched in favour of something quite monstrous.